Kids Greening Taupō’s 10th birthday on Saturday (September 20) at Spa Thermal Park was an opportunity for those who established the organisation and those running it now to reflect on how it had survived and its continued success.

Ultimately, they said, the key was the program’s ability to be adapted to suit circumstances.

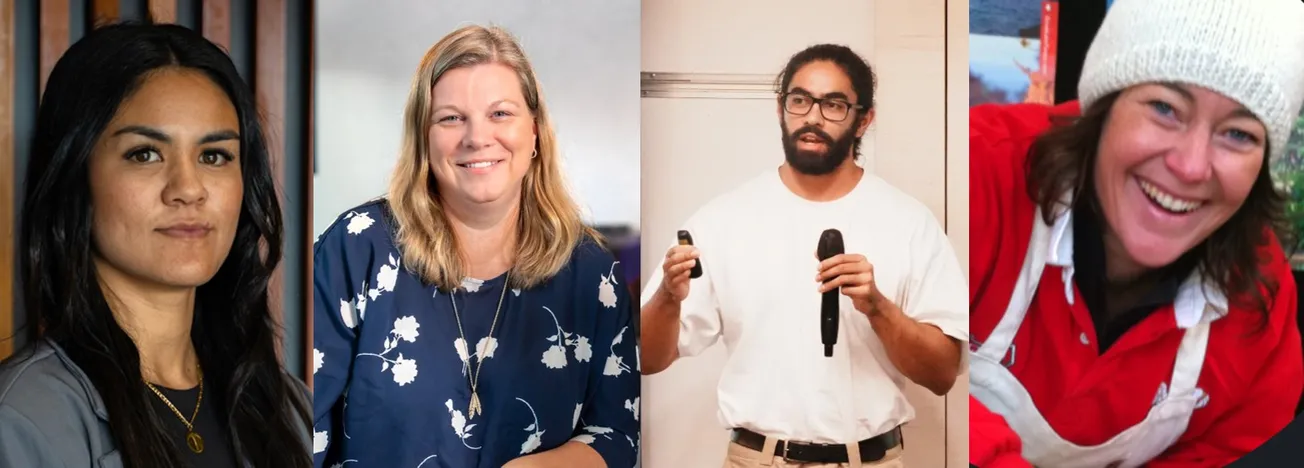

Also featured were the glowing testimonials of several past students for whom KGT had played a formative role in the study paths they have embarked on.

Current lead education co-ordinator Rachel Thompson introduced several original organisers such as Nina Manning and Tanya Weld from the Department of Conservation (DOC) who were part of a group, including local teachers, who had observed a model in operation in Te Anau and were inspired with replicating it in Taupō.

Manning said from a kindergarten on bush kindy day, the group visited a primary school checking traps before going to a high school, and a student leadership meeting.

“It just sort of blew our minds… we wanted to establish something like this in Taupō.”

“For me personally, it's been one of the most rewarding things that I've been a part of and to see it today 10 years later is amazing.”

Weld said the group realised early on it would need to draw in others – including from organisations like Project Tongariro, central and local government, iwi and schools.

“The reason we tapped them on the shoulder was because they were pretty talented people, but they also were from different agencies,” Weld said.

Having the involvement of Thea de Petris was also key, she said.

“An awesome young lady who was an environment education specialist who was looking to further her studies at Waikato.”

Key ingredients in the recipe the group wanted to see instituted, said De Petris, were: real life learning opportunities, collaborative partnerships between schools and community, and a student led approach.

“Giving our young people the opportunity to be in the driver's seat as community leaders.”

By happy coincidence KGT became the research project for her master's studies in education.

She became a regular participant at meetings and events for the 18 months before the official launch, documenting successes and challenges.

Significantly the organisation had no funding when it started the pilot.

The working group and first student leadership team performed the amazing feat of getting the program off the ground with absolutely no capital input, she said.

“The shared vision of getting KGT up and running with funding, that was the glue that held us all together.”

However by the end of that 12 months, the workload had begun to take its toll and volunteer fatigue was setting in until a one off lifeline grant from DOC.

“We were able to hire a part-time coordinator, Amanda Jones… and she was able to take a whole load of stress off the stakeholders. Soon after, to everyone's relief, the program was awarded its first significant multi-year funding grant and officially logged in October 2015.”

KGT's progression, structures and processes was a demonstration of the collaborative community education model (CCM), said De Petris, successful enough to be replicated in programs elsewhere in Dunedin, Taranaki and Wellington.

When she later took over as KGT’s third coordinator, she moved from researcher into putting theory into practice.

“For the most part, we were successful, we were able to secure some additional multiyear grants and sponsors and transitioned from five to 12 schools.

“Another highlight was working alongside Sian Moffitt, who was a student leader, then onto a volunteer for KGT when she came back from university and then became a paid staff member.”

In an excerpt read out by Thompson, Moffitt said KGT had completely reshaped her career path from planning to study design and photography to pursuing a Bachelor of Science and ecology, biodiversity, and environmental studies.

This testimonial was backed up by ones from former student Katherine Davy, another science graduate, and current KGT member Kaiao Marino.

Reflecting on the 10 years highlighted several issues, said De Petris.

“Should it be individual restoration projects or collective restoration projects or both? And how do you get the best out of your student leaders when you only get to meet with them once a month? … I sometimes got frustrated that we didn't have all the perfect ultimate answers. But… I see now that this is where the goal was and remains for KGT, that it's a program that continuously evolves and adapts through opportunities created by strong local partnerships, and relationships.”

Thompson, despite being interrupted by the loud call of a Shining Cuckoo (Pipiwharauroa) from a nearby tree, backed up the idea that KGT had morphed and changed over the years.

“Not only are we about planting trees, doing the weeding, doing the maintenance, but we're out there looking at freshwater macro-invertebrates, talking about how we can improve our waterways, talking about invasive clams, biosecurity, predator control, trapping. We're introduced biological controls from other areas of New Zealand. We do Kiwi tours… We talk about wetlands. I could go on and on.”

The organisation could change to meet the needs of our community, she said.

“We can do that because our funding allows us too. So a very special thank you to Taupō District Council, Waikato Regional Council, Contact Energy, Bay Trust, Mitre 10, Tūwharetoa Māori Trust Board... and others I’ve missed.”

Also marking the event was the mayoral unveiling of a sign celebrating the organisation’s achievements, near an original student leader community planting in 2017 as well as a small planting, activities and a nature-themed cake competition.

Podiatry at Tōtara was a major sponsor of the celebration while Kona Kones, Sue Graham from Wildwood Gallery and Peak Strength donated cake competition prizes.